This summer I’m excited to be teaching Introduction to Creative Writing through the Continuing Education Program at North Seattle College. I designed this course in response to the many people who told me that they’d like to write but don’t know how to begin and those who want to rekindle a writing practice. All of us, regardless of experience, will be writing with beginner’s eyes, myself included. This 6-week course is for anyone wanting to play around with words in the community of others, create original writing in any genre, and develop a regular writing practice that they can take with them after the class ends—a kind of Moveable Feast that can go anywhere. Class begins Friday, July 11.

-

To Return

I.

I’m sitting on the shores of Lake Washington, amazed at what I can do. I recently finished a solid draft of my second novel. Today I danced hard, biked to the beach, swam in the green-blue waves, and will later have to bike back up all those hills to home. But I can do it. My body and—miraculously—my mind are in the best shape of my life.

Not bad for someone who’s come back from the dead.

Coming back isn’t an accurate way to put it though. I died two years ago when I was diagnosed with an aggressive ovarian cancer. I was burnt down, ash of myself sifted through the hands of my doctors and nurses and those who cared about me. Now a new self is writing this—someone I don’t quite recognize, but who I love and want to get to know.

II.

I was diagnosed with clear cell carcinoma in May 2021, a few days after my second COVID-19 vaccination shot. After my surgery the next week, removing (along with all of my reproductive organs) a 14-centimeter tumor from my body, I spent a lot of time watching movies and trying to read as I convalesced. I noticed something I never noticed so much before—cancer is everywhere in books and movies. Sometimes it’s a main event, like in Big Fish, and other times it plays a cameo role or hovers in the shadows. But it is almost always there.

I think fiction takes on cancer because it’s a nearly universal experience—everyone has either experienced it first-hand or knows someone who has experienced it. Giving a character cancer can make them change (or die), move or twist a plot. It can work as a believable deus ex machina in reverse, since anyone at all can suddenly have cancer, no matter how healthy, rich, or smart a person is. A very healthy person can get it (like myself) and it’s a toss-up whether they will get better (like myself) or die of it.

Cancer is nearly universal—but when it happens to you, the journey you go on is yours alone. And it seems totally unbelievable—a case in which life is stranger than fiction.

III.

In my journals of that time, I described cancer as a failure of the body. But I don’t think it is. It seems more like an overexcitement of existence, so many cells dividing that they threaten the organs we need to live. Cancer is part of being a multi-cellular organism—it’s the risk of being alive. Perhaps the disease could be considered a type of creativity. The body births a strange beauty of extra cells, which collect into sculpture-like tumors. It creates its own blood supply to feed its dangerous art form. There is some kind of care taken to tend to the tumors, to assure their longevity and growth—while the rest of the body, the body that wants to live, wages war.

Nephron, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Looking at images of clear cell ovarian cancer cells, I can appreciate their strangeness—even their beauty. Stained, they can look like marbleized paper, or abstract painting, or globs of dripped paint. Sometimes, they look like knitting, a shawl made not for wearing, for it won’t keep out the cold, but for its design alone—for the many open spaces.

IV.

Surgery first emptied me out, then chemo gutted and hollowed what was left. At my most empty, I had no idea if I’d return from this. And if I returned physically, would my mind?

On a trip to Whidbey Island with my partner at the time, we met a friend of his I’d never met before—an acupuncturist who took one look at me and said, “That woman you were—she’s not here anymore.”

V.

I’m in a bikini on the beach, waves lapping my toes. The new moon stamps the sky. A thick scar begins at the delta of my stomach and curves around my belly button all the way down—a kind of seam where the dangerous sculpture was extracted. Where I was sewn back together, made into another art. It’s a single line painting by Miró. It contains a story, marks the point of no return. It’s the pain of a cracked egg and the beauty of birth. It’s what’s left of the woman I was, and from where I birthed a new self.

My hysterectomy scar and Miró’s Painting on white background for the cell of a recluse (I), 20 May 1968, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona I’m no longer self-conscious of this scar, or feel it’s worth hiding from others. It’s etched on me the way Mt. Rainier is etched in the sky today, every glacier visible and clear.

VI.

The toxic medicines used to stop my over-exuberant cancer cells also seemed to stop the creativity in me for a time. It was the emptiest time. At least, that’s how I remember it.

My friend and writing partner, Suzanne, came to see me every third week—which was my best week—after chemo. She came bearing sunlight, fattening snacks, her laptop and notebooks. We’d make a picnic and sit together out in my courtyard or at my dining room table, be in each other’s silence and presence, and write.

The process of writing is blank in my mind. I know I worked on a story about the Soviet invasion of Prague, a moment that changed all of my characters’ lives irrevocably and forever. The tanks rolled in like rampant cancer cells, and nothing would ever be the same again.

I felt like I was mimicking myself—the self I remembered from before. Before, I wrote. I was a writer. But who was I now? I was just typing, trying on a writer’s coat in the presence of another writer. I clacked on the keyboard, stringing letters into words, and words into sentences. So this is what a writer does, I thought. Clack, clack, clack. Clack.

VII.

I didn’t know, but I was stringing together a path to return. Like dropping stones to find your way out of a deep, dark wood.

VIII.

Later, after the big bad chemo was over and I was on my year of chemo-lite, I opened the file of my novel-in-progress to see if it would have any meaning for me now. My brain was still repairing from the damage the chemo caused and together with massive anxiety, I could only focus for a few minutes at a time, so it took me a while to get back into the material. When I did, I was surprised to find passages I didn’t recognize. I had, apparently, also worked on the novel in my sessions with Suzanne.

I rediscovered that much of the book centers on the concept of identity, as the characters are guinea pigs for a Witness Protection Program so nascent it has no name yet. I found a note in the margins I’d written a few years ago: “If you get to live, but don’t get to be who you are—is being alive worth it?”

IX.

It was like I was writing to my future self, whoever that would be—like I had known what was going to happen to me. Somehow, I knew I would need this—that note, this novel about identity—to help me find a way to a self.

While my characters were grappling with their multiple iterations of selfhood, I found my answer to that marginal question—a resounding fuck yes.

X.

Returning, I realized, isn’t about going back.

It’s about picking up stones, one at a time, marveling at their shapes, their heft, their colors—their aliveness.

-

Focus, Focus

We need to keep creating art. Especially in these hard times. Trust me on this. We need to be there for each other in all ways. —Kelli Russell Agodon, via Twitter

In a recent virtual literary happy hour presented by Hugo House, guest writer Marie-Helene Bertino mentioned that focus was a scarce commodity these days. “Collective grief really ruins attention spans.”

That was the first time I realized that I might be grieving. I didn’t know I was grieving my old way of life, grieving for all the lives destroyed. And, as the weeks progressed, grieving for Black and Brown lives, grieving for all the harm this country has inflicted and continues to inflict, grieving for my own white ignorance and complicity—grieving for all the hundreds of thousands of dead.

Joan Miró, Painting on white background for the cell of a recluse (I), 20 May 1968, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, Spain. What I did know was that I was having trouble focusing on my own writing. It suddenly seemed so small and meaningless compared to the many life-and-death situations of others. In the early stages of the pandemic, I thought I would be able to make good progress on my next novel, but I found myself wondering why I was writing this and if it meant anything. The only thing I could focus on was food and scarcity. I checked my cupboards and inventoried my food stores so often the pulls on my cupboard doors fell off. But I couldn’t think much about my book. Then, as the death of George Floyd spurred protests and awareness around the world, I further wondered what my as-of-now sprawling book about identity and lost fathers mattered at all.

What made things worse was that many people in my orbit seemed to be getting a lot of work done. Friends and artists I know were making art in response to the pandemic and the Seattle protests; others found solace in their writing—and all of this made me feel not only incredibly envious but also defective somehow. Why couldn’t I sink into my writing the way I’d always done?

But I soon realized I was not alone. In R.O. Kwon’s opinion piece in the New York Times, she writes that the pandemic stopped her speaking gigs and travel so she finally had the time and space to work on her novel. “But,” she writes, “I couldn’t focus. What’s more, news aside, I could barely read. . . . I couldn’t recall why I’d even cared so much about books, words.”

This was how I was feeling, and reading this helped me further acknowledge the grief. My perspective shifted. I needed to grieve. I learned too that I needed to take everything slowly. Allow myself the freedom to write any words or no words at all. To sit and do nothing, or draw instead. To cook meals and read what words I could. The first novel I could finally read beginning to end was The Fish Can Sing, by Icelandic writer Hallador Laxness, about a boy who aspired to sing. It was a soothing balm for the grief, and for finding my voice own again.

I could think about art again. Extremely encouraging were tweets from poet Kelli Russell Agodon, reminders that art matters and we must continue to do our work. Someone needs it. We may not know who. We may not know why it matters. But it does.

She writes:

For those of you who are grieving—grieve on.

Do not ignore this pain, it is a reminder of who we need to give power to and that we need to take care of each other. To stand up, to say—No, this should not happen.

Be brave. Speak up. Make art.

For some reason, I remembered sitting before Miró’s single line paintings at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona just over a year ago—the Painting on a White Background for the Cell of a Recluse series. How I sat and absorbed a single line at a time, doing so because I didn’t understand them. I came to slowly see that a single line can be everything. Can have power. Can tell an entire story. Can be enough.

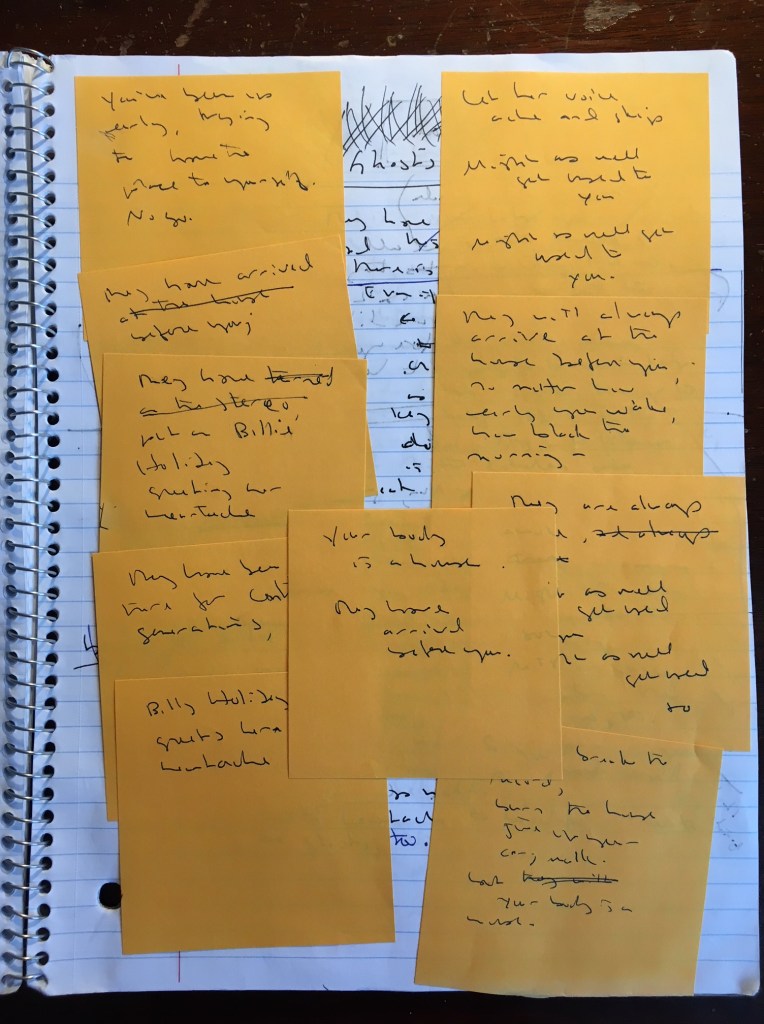

I began to write words and phrases on sticky notes. These became lines, which I arranged and rearranged in my notebook. I found I could focus on a single word, or a single line. These eventually became poems—poems, I realized, that centered on anxiety and grief. I just let the lines happen, good or bad, and in that way found myself slowly on the journey back to my book.

Lines that eventually became the poem “Ghosts.” I’m not saying I can focus well. And I often don’t make my goal of editing or writing 500 words when I sit down to write. But I trust. I trust the work I’m doing. I may not know what it means or why it matters—all I know is that I need to write it. That is enough, and what it means, how it speaks to others, what it means to others will be revealed in the process. It will show me, if I let it, what it has to say.

-

Notes and scraps: building a piece of writing

I am fascinated by the notebooks of writers and artists–the doodles, bits of research and notes to self, the handwriting, the bad early drafts. There is something necessary in the sheer chaos of a notebook or a box of clippings, scraps, and other ephemera. So much goes into the making of a book, a story, a single poem.

A notebook I used while writing The Good Sister Even my own notebooks and file boxes fascinate me. Sometimes I have no idea who that person was who wrote all those notes, clipped so many articles, drew so many pictures, used so many different colors of pens, cut up passages and taped them together in reverse order. Writing envelops you when you’re in the midst of it, seals you right up with it. It can be useful to see, especially when embarking on a new project, that a good piece of writing often begins in a big mess with quite a lot of bad writing involved.

That’s also partly why I love looking at notebooks and early drafts of work by writers I admire. While I was in Dublin a few Junes ago, I was lucky to see a William Butler Yeats exhibit at the National Library of Ireland (The Life and Works of William Butler Yeats), where a lot of early, handwritten drafts of his poems were shown. Wonky handwriting, strikethroughs, botched titles: it was comforting to know that even the greatest of writers can sometimes begin a little off, or take wrong turns. Yeats’s “Crazy Jane” was earlier named “Cracked Mary.” Cracked Mary had made it as far as a typed draft of the poem, but Jane hovers, handwritten, in the margins, then takes over to finally become its title, “Crazy Jane and the Bishop.”

Every piece of writing you see in print–final, published–looks clean and simple, every word in its place. But its history is likely chaotic, beginning in a kind of Pandora’s box, in the disjointed form of clippings, photographs, diary entries, diagrams, and notes, all clamoring at the lid, wanting to discover what it all means.

And even when the writing is published, perhaps it is never perfect. At a Colum McCann reading for Let the Great World Spin, he stopped in the middle of a paragraph, read it again, reread it, and then finally, chagrined, he looked out over his audience and asked if that sentence made any sense. “No,” he answered for us. “No, it doesn’t.” That sentence had managed to hold onto its chaotic beginnings, giving us readers a glimpse inside that box.

-

Imposter Syndrome

When Storyfort, the literary component of Treefort Music Festival, offered to host me, and then put me on the main stage with the amazing Lidia Yuknavitch, I freaked out. I might’ve even jumped out of my chair and laughed out loud. I just had to tell someone. Right away. The first to be blindsided with the news was a co-worker of mine, just because he sat nearest to me.

“Who’s that? What’s Storyfort?” He shrugged uncomfortably. “I don’t know what any of that is.” He turned back to his computer.

If I was disappointed by his response, it didn’t register. I was too excited. I couldn’t believe that of all people, I would get to read with the writer I most admired in the festival lineup. Lidia Yuknavitch. Man.

By the next day, my excitement made way for another feeling—unease. A voice in my head kept asking me: Who did I think I was, anyway? Who the hell am I to be sharing a stage with Lidia Yuknavitch? I answered with: I’m a writer, that’s who. I’m worthy. Surely I’m worthy. I am. Really.

“Ah,” my friend Suzanne said over drinks that night. “A serious case of imposter syndrome.”

But if there is any place to feel unworthy, to feel like an imposter, it’s in the room with Lidia Yuknavitch, a self-declared misfit. (Read The Misfit’s Manifesto and watch her TED talk. I know it made me feel a lot better.) Being a misfit—or someone who has “missed fitting in,” as she puts it—has been her entire life.

And thank god she’s a misfit. She writes like no other—with raw, honest, brutal and loving intensity. Her writing might make us uncomfortable and it might kill us, but her memoir, The Chronology of Water, is one of those rare books that cuts straight to the heart of what it means to be a human being.

-

For what it’s worth

Pickled letters at a graphic design studio in Istanbul. I’ve been quiet since the presidential election. Like many people, the election threw me—not because I didn’t think he could win, but because I couldn’t imagine it. Me, a fiction writer who speculates about nearly everything, playing out what ifs, the outcomes and meanings of various scenarios in my head, couldn’t imagine what the United States would look like with Trump as president. And after, I took it as a national and personal tragedy, thought I’d never feel happiness or hope again. As well as taking a close look at my country, I looked at myself, my life, my work. My fiction writing. And I wondered what it was worth.

Several people told me: You’re a writer. You have the power to influence people and promote change. Use your skills. So I felt this pressure, this obligation to write essays that would move people to take some kind of action. I felt the importance of my fiction writing diminish in the face of such dire times. Unless I was writing something like 1984, writing fiction felt indulgent, frivolous.

In an interview with Turkish novelist Elif Shafak on the New Yorker Radio Hour, David Remnick commented that it seemed like she was writing about politics in spite of herself—almost against her will. She replied that she doesn’t have the luxury to not be political, given the oppressive situation in Turkey and the fact that she’s Turkish.

Writing at Istanbul Atatürk Airport I also felt like I was writing about politics against my will, and I also felt that same obligation as an American who believes in protecting—and fighting for—equality and civil liberties. To protect the ability to criticize, state opinions without repercussions, and yes—write whatever we want.

And that’s key. When I spent some time in Istanbul last November, I learned from Turkish artists that one of the most rebellious things you can do to protest a political system bent on killing free expression is to keep doing your art. Thinking, writing, creating—are dangerous to the regime. When author and badass Naomi Klein was last in Seattle, she remarked that it was important to not just say no to the Trump agenda. We also need to “fiercely protect some space to dream and plan for a better world. This isn’t an indulgence. It’s an essential part of how we defeat Trumpism.”

After writing essays, letters to representatives, and valentines to Washington State mosques, I began to incorporate fiction into my writing life again, cultivate it, let it take up more space. And it feels goods. Fiction’s my home. It’s the best way I can be a part of the world. Stories make us human, help us understand one another, provoke us to ask questions. Exercising this civil liberty is active protest. And it’s worth everything.

-

There Is Time

At a recent reading at the Seattle Public Library, Colson Whitehead said of his new novel, The Underground Railroad: “I wrote this book when I was ready to write it. I wouldn’t have been able to fifteen years ago.” The idea came to him back then, but said he knew he wasn’t good enough to write the story.

In a moment when I’m looking at the scraps and beginnings of a second novel, when I’m feeling the pressure of age and mortality, feeling in a hurry to get all these ideas out before I die, it’s good to keep in mind that there is time—and regardless, the work will come out when it’s damn well ready to. And you want it that way. Really.

The two must converge: Your skill as a writer and it as an idea. I think of how it would be had I attempted to write The Good Sister in my twenties, when I’d just returned from Mexico and was living in a friend’s basement, trying to adapt to my new/old world while trying to make sense of the experience I’d had. It would’ve been a terrible book along the lines of my angsty journals, if it had been able to cohere at all.

Sometimes I scold myself for not having worked harder on my writing in my twenties, that I should have worked through the post-college bewilderment via pounding out a book, putting my writing career in motion much earlier than at say, forty. But I know I couldn’t have completed my first novel sooner than I did. It needed all that time. It needed seventeen years.

Had Whitehead gotten ahead of himself and tried to write The Underground Railroad when he got the idea, he said he would’ve screwed it up. So he shelved it, trusting there would be time. In between then and now (and now the novel is on the National Book Award longlist), he wrote other novels—got a little better, failed, had a relapse, got a little better…

A moth flitted about in the light, eventually circling down to Whitehead as if to look him directly in the face. He laughed and gently brushed it away. “My spirit animal,” he said.

-

Vancouver: The Good Sister book launch

Having spent a lot of time going to readings and talks, it was strange to be on the other side, looking out at the audience rather than being in the audience. As I stood there at Book Warehouse Main Street in Vancouver preparing to read, I remembered a couple of things heard and overheard in Seattle before I left for this event.

Random guy in Cal Anderson Park, talking to his friends: “When you go in there, you’re nervous, right? So what I do is slowly scan the crowd…then they get nervous.”

Poet Cedar Sigo, at the Sorrento Hotel for the APRIL festival: “A nervous breakdown and a good reading are closely related.”

I didn’t put either of those things into practice that night (not intentionally, anyway), but any form of nervousness I might’ve felt was drowned out by a lot of love—from my parents and aunts who made it up to Vancouver from eastern Washington; from my friend Yukmila who flew out from Washington, D.C.; from UBC Creative Writing co-chairs Annabel Lyon and Linda Svendsen, as well as so many friends and allies who helped with the book; my agent, Dean Cooke, who flew all the way out from Toronto; from the lovely, gracious folks at Book Warehouse.

There was also the incredible Minelle Mahtani, host of the 98.3 Roundhouse Radio show Sense of Place, which I was on the following morning. She surprised me during the interview with a clip she’d recorded of my dad talking about my writing.

All came together to make a wonderful book launch, despite the rain clouds that gathered outside the door after a bright, sunny day. And the rain did eventually come. But it didn’t bother us. We made our own light.

-

Happy Birthday, debut novel! The Good Sister is now on sale.

Here. It. Comes. When I first held the completed, printed, real-book version of The Good Sister in my hands, I burst into tears, overwhelmed. In between the (may I say lovely) front and back covers are years of not only writing and editing, but years of life—beginning in 1993, when I first travelled to Mexico City, and on through 1999, when I lived in Baja. Those were the beginnings, but I did not know then I would write a novel. Add to that grad school and jobs and relationships and a whole lot of life changes, this book that isn’t about me oddly contains so much of my life. Then I thought of all the people, more than I can name, who contributed in one way or another to this book, to the stories within the book. Stories that go far beyond these pages.

And what pages they are! Soft and deckle-edged, smelling of new ink. I turned them, marveling that the book had pages. Then I freaked out over page numbers: My book has page numbers? Each sentence is affiliated with its own specific page number? This is amazing! I imagine this might be what it’s like for a mother to hold her newborn child, marveling at the fact of the baby’s toes and ears and nose.

So here it is—world, this is The Good Sister.

Good Sister, this is the world.

-

All Is Fair…

At the Hugo House Literary Series in April, novelist Andrew Sean Greer introduced the story he wrote for the prompt (“All is Fair in Love and War”): “I haven’t read this piece,” he said. “Not just aloud—but at all.”

Earlier, my friend Erin Fried and I were talking about how some people can offer up what they write as soon as they write it. For National Poetry Month, friends of hers wrote a poem a day and posted every single one online. Erin was exasperated. “How can they do that?” she asked, meaning: Why can’t she? For so many of us, it takes a while to feel a piece is good enough to show others. That’s normal. But it made me wonder how much of that is perfection of craft, and how much is fear about how it will reflect us: If the piece isn’t good enough, then neither are we. I agonize over every bit of writing before I put it out there—even this blog post. But what if, just for a while, I didn’t?

For one, it might be really fun. As Andrew Sean Greer read, he was as surprised and amused at elements of his story as the audience was. It was also revealing—Greer could only be himself, the act of writing exposed. Weird turns he took in his story and didn’t remember taking made for a kind of crash performance where anything could happen.

It struck me as rather brave. When I mentioned this to him after the show, he said he could to do it because he’d just turned in a novel he’d been working on for years. It felt so good to work on something that wasn’t the novel, he said—it was like going out and having wild sex again. “Not that I know what that’s like,” he added. “I’ve been married for 20 years now.”

I just completed my first novel, The Good Sister—it is at the printers’ as I write this—so I can understand a bit of what Greer is talking about. I do feel release as I begin embarking on a whole new project open to limitless possibility. However, I still find myself bound to shoulds—“marching orders,” as writers Ryan Boudinot and Aimee Bender call them. Some kind of boss in you says you should write about one thing, while your heart is aching to write about another. The boss’s voice is really loud; I end up succumbing too often.

This time, though, I’m putting up a really good fight. The writing is really fun, and I aim to keep it so. The agonizing can—and will—come later.